‘If it can work anywhere, it’s here’, says Jasper Klapwijk, the enthusiastic expert in energy policy. Introducing: Sporenburg, a neighbourhood with little more than five hundred houses in the Eastern Docklands area of Amsterdam.

Sporenburg is one of the urbanized peninsulas east of Amsterdam Central Station, where there used to be an industrial ore transshipment hub, located directly south of the now densely populated district, where cars race invisibly through the Piet Hein tunnel, the traffic artery that lies nearby under the water of the IJ-river.

The Amsterdam pilot of RESCHOOL is coined ‘FlexCity’, an innovative pilot for which almost a hundred homeowners in the district have now signed up. They have a dongle installed , which transmits the household power consumption data per second to a server. In addition, all participants have an app on their smartphone or tablet , which gives them ‘live’ insight into their consumption. Participants are rewarded if they use electricity for their washing machine or dishwasher during sunny hours, and do not do so at times when there is a peak in the power grid.

The aim of all this is to investigate whether it is possible to smooth out the peaks in power consumption, and to do so in a geographically narrowly defined area: a transformer house of grid operator Liander.

This inconspicuous transformer, sprayed with graffiti, is the electricity heart of this Amsterdam district. The energy transition requires thousands of these man-sized buildings to be added in the Netherlands. ‘Replacing a transformer house costs four hundred thousand euros,’ says Hugo Niesing, one of the other driving forces behind the pilot. It will therefore save society a lot of money if residential areas succeed in organising their energy consumption in such a smart way that fewer transformers need to be installed.

Niesing lives on a houseboat near the adjacent Borneo peninsula. With his company Resourcefully (one of the partners of RESCHOOL), he has been hired by the municipality of Amsterdam for years to roll out the smart charging station network in the city. He is closely involved in setting up the charging stations as efficiently as possible; So that power peaks are avoided and cars can be fully charged at less power at the busiest hours of the day. Since last year, he has also been one of the technical people behind the pilot in Sporenburg.

But back to Jasper Klapwijk, who explained why Sporenburg is the ideal place for this pilot. ‘When this area was redeveloped in the 1990s, the municipality was convinced: yuppies will live here. So here come apartments without kitchens and only microwaves; Because those people go out for dinner in the centre anyway. Well, the reality turned out to be somewhat different. Some of the facilities that the municipality had not drawn up in the neighbourhood were taken up by the residents themselves. There was no church, there was no community centre, there was no retirement home, no school was conceived. So that neighbourhood became incredibly self-reliant.

Klapwijk: ‘At that time, a neighbourhood cooperative was set up around a community centre that the residents themselves set up in an empty office building, which they have now also bought. In 2019, there was a neighbourhood summit there, where a neighbourhood agenda was drawn up. One of the priorities was sustainability. That neighbourhood agenda has been taken over one-on-one by the district, which is really great. It’s rare for something like this to be embraced without scratching it.’

This ‘co-reliance’ of the neighbourhood is important for step two of the pilot in Sporenburg: the establishment of an energy cooperative. First of all, the aim is to avoid power peaks by encouraging flexible behaviour among households, which in the ideal scenario are even financially rewarded by the grid operator. Because it means they don’t have to install an expensive transformer.

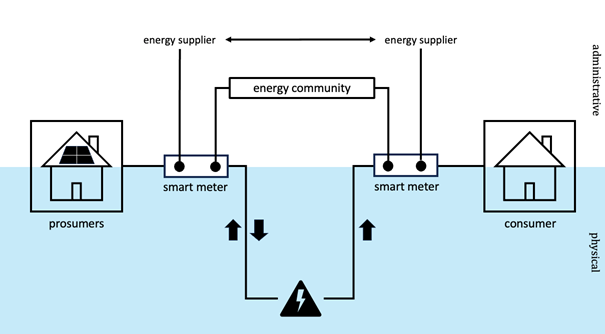

But the dream is even bigger. In Sporenburg, thanks to an energy cooperative, it should be possible to share energy with each other. ‘This is already happening at the electron level’ says Jasper Klapwijk. ‘If I have panels on my roof, and my neighbour has a charging station, my excess electrons go to my neighbour. They never reach the transformer house. So in physical reality, this is already happening. But you also have to be able to account for it administratively.’

In fact, the idea is simple. If a household is a net producer (the solar panels generate more than the consumption, measured on an annual basis), they can sell this surplus electricity to households that are net consumers. This will ensure that a win-win situation will be created.

This means that the net producer gets a better price for its surplus power than the supplier, and the net consumer pays less for the neighbourhood power than with his supplier.

Currently, this direct energy sharing is cumbersome and non-existent. A cynical reason is that energy suppliers simply don’t make money on this. And the upcoming new Energy Act does not make this much easier. However, the current Dutch Minister for Climate and Energy Policy Rob Jetten has announced that avoiding congestion is one of his priorities.

In the meantime, FlexCity will demonstrate what is already possible. ‘We challenge the regulations’, is how Klapwijk puts it. ‘We do what is technically feasible within the regulations.‘

Everything about the Amsterdam pilot can be found here. If you are curious about the latest news of the RESCHOOL project, please check out website and follow us on LinkedIn and Twitter.